15 November 1977, Niigata, Japan:

1977년 11월 15일, Megumi Yokota가 배드민턴 게임을 즐기고 난후, 황홀한 일몰이 비쳐지고 있던 그이후에 일이 벌어졌었다. 찬바람은 Niigata현의 어촌에 불고있었고, 회색의 바닷물은 모래사장에 넘실대고 있었다. 불이 켜져있는 그녀의 집까지는 약 7분 거리에 있었다.

처음에 이사건에 터졌을때, 일본정부에서는 전연 믿지 않았었다고 한다. 이사건이 알려지면서, 그동안 속만 끓이고 있던 비슷한 망연자실한 상황에 처했던 많은 부모들이 나타났었다고 하며, 그때에서야 일본 정부가 관심을 갖고 문제 해결에 나서면서 당시 수상 Junichiro Koizumi씨가 북한을 방문까지 했었다고 한다.

당시 13세였던 Megumi양은 책가방과 배드민튼 라켓을 메고, 같이 플레이했던 두명의 친구들과, 그녀의 집으로 부터 약 800미터 떨어져 있는 곳에서 "잘가 또보자"라는 인사를 하고 헤여졌었다. 그러나 그녀는 그뒤로 집에 도착하지 못하고 그것이 마지막이었었다. 오후 6시가 지나 7시가 되여 조용한 거리는 그녀를 맞이하는데 실패하고, 엄마 Sakie Yokota씨는 패닉상태에 빠져, 그녀가 걸어서 올것으로 기대하면서 Yorii중학교로 달려갔었다.

"그아이들은 오래전에 학교를 떠나 집으로 갔어요"라고 야간 담당 보안관은 알려줬었다.

경찰, 훈련견, 그리고 휏불까지 동원하여 거리를 밝히면서," Megumi야, Megumi야" 불러대면서 주위와 인근의 소나무 숲을 이잡듯이 뒤졌었다. Sakie씨는 바닷가로 달려가 주차되여 있는 모든 차량들도 살펴 봤었다.

해안가를 따라 샅샅이 뒤졌지만, 그날밤에 엄마는 믿기지 않는 기절초풍할 그무엇을 느꼈었던 것이다. 일본 해안 깊숙한 저넘어에는 북한간첩으로 보이는 보트가 전속력으로 한반도를 향해 달리고 있었고, 그배에는 납치되여 무서움에 떨고 있는 여학생이 캄캄한 조금만 창고에 갇혀 있었던 것이다. 그들은 증거가 될만한 아무런 흔적이나 이광경을 본 증인도 남기지 않고 보트를 타고 도망친 것이다.

이렇게 아무런 증거도 찾지 못한채 몇년이 흘러가면서, 이러한 범죄의 희생양이 된것은 Megumi 뿐만이 아니고 여러명이라는 사실이 확실히 세상에 알려지게 됐다.

그러나 일본 정부는, 이사건이 일어난 해인 1977년부터 1983년까지, 북한 공작원들은 17명의 일본인을 납치했었다고 발표 한것이다. 일부 전문가들은 실제로 납치된 일본인들의 전부 100명이 훨씬 넘을 것이라고 믿고 있다.

Megumi양이 사라진 이후로 경찰은 총인원 3,000명을 동원하여 수색을 했었다. 납치조는 Yokota 씨의 집에 상주하다시피했었고, 해양순찰대는 일본해를 이잡듯이 수색 했었다. 수색은 계속됐었지만, 해결책은 하나도 없었고, 분노만 커져 갔었다.

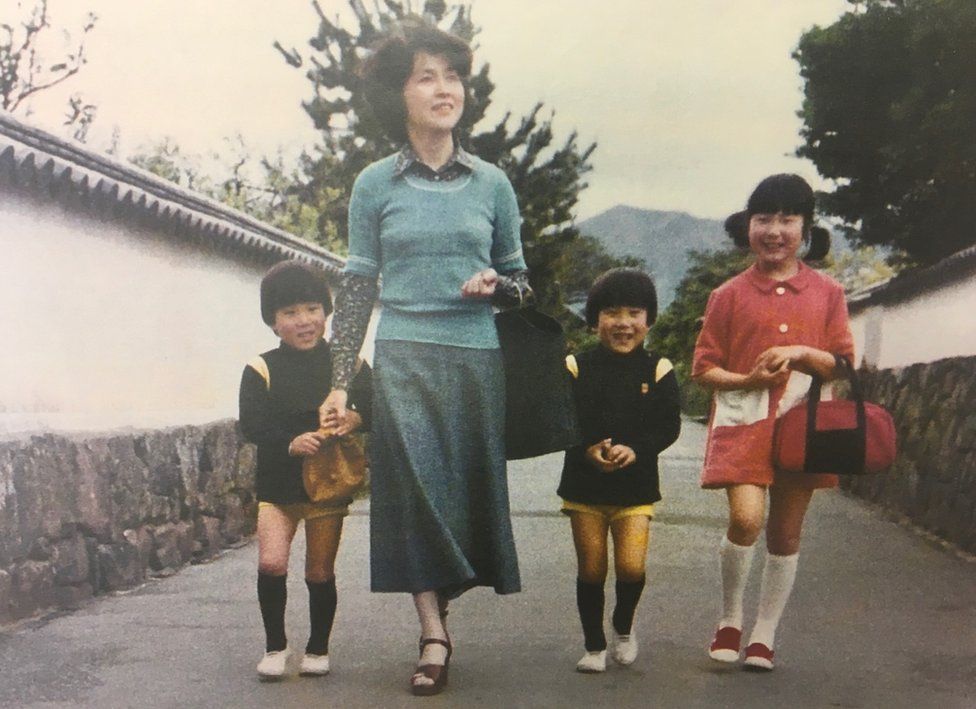

Megumi양의 아버지, Shigeru씨는 아침마다 바닷가 모래위를 걸었었고, 밤에는 목욕탕에서 물틀어놓고 통곡을 했었다. 엄마 Sakie씨는 혼자 있을때마다, 행여나 Megumi의 9살된 쌍둥이 남동생들이 눈치채고, 들을까봐 흐느끼면서 세월을 보냈었다.

모래시계는 Yokota 가족들을 변화시켰다. 수년동안 그들은 소용없는 그짖을 무심코 하곤 했었다. 다행히도 납치된 Megumi양은 살아 있었던 것이다.

1993년에 남한으로 탈출한 북한 공작원 한명이 서울에서 기자회견하면서, 납치되여 이북에 있는 일본여인이 정확히 Megumi와 모든 상황이 일치 한다고 자세히 설명한 것이다.

"나는 그녀를 아주 선명히 기억하고 있다. 나는 젊은 청년으로서, 그녀는 매우 아름다웠었다"라고.

그는 설명하기를 그녀를 납치한 공작원중 한명(고참 공작원 메니져)이 그에게 1988년도에 그녀에 관해서 자세히 얘기를 해 줬었다고 폭로한 것이다.

"처음에 납치는 계획에 없었던, 멍청한 짖이었었다"라고 그가 설명한 것이다. 아무도 어린 꼬마 소녀를 납치할 생각은 하지 않았었다. 두명의 공작원이 스파이 미션을 마치고, Niigata현의 바닷가에서 그들을 태우고 북한으로 돌아갈 보트를 기다리고 있었다. 그들은 우연히 길을 걸어가는 소녀를 목격한 것이다. 두려웠지만, 그들은 그녀를 붙잡았다. 그때 Megumi양은 나이에 비해 키가 컸었다. 사방은 어두웠기에 그녀가 꼬마학생인줄을 알수가 없었던 것이다.

1980년 1월 7일, 산께이 신문은 일면 톱으로 "3 카플이 며칠사이를 두고, 아무도 알지 못하게, Fukui, Niigata, 그리고 Kagoshima현의 해안가에서 사라졌는데, 아마도 외국의 공작원들이 이납치극에 가담한것 같다?"라고. 마침내 북괴 공작원의 범죄행위라고 밝히는데는 상당 시간이 걸렸었다.

김현희가 1987년도에 115명을 싣고 한국으로 되돌아 오고 있는 대한항공비행기에 폭탄을 몰래 반입하는데 성공했다. 그후 그녀는 서울로 압송되여, 재판에서 사형을 선고 받았었는데, 그녀는 자신이 북한 공작원으로 북괴의 지령을 받고 비행기를 폭파 했었다고 실토했다.

그녀는 일본어와 일본풍습을 배웠기에 비밀 공작원으로 활동할수 있었다고 실토한 것이다. 그녀를 가르친 선생은 일본으로 부터 납치당한 일본 여성이었으며, 그 일본인 선생과 거의 2년을 같이 먹고 자면서 생활했었다고 실토했었다.

1997년, Megumi양이 실종된지 20년이 지나서, 평양측은 마침내 이사건을 조사하기로 합의 한다.

21 January 1997

"우리는 당신의 딸이 북한에 거주하고 있다는 정보를 갖고있다"라고.

Shigeru씨는 깜짝 놀랐다. 일본 국회의원의 개인비서로 근무하고 있는 Tatsukichi Hyomoto씨가 절망에 빠져있는 Yokotas 씨 부부와 접촉하게된다. 그는 10년 넘게 평양측이 납치한것을 밝히기위해 찾아 헤맸다고 설명하면서, 가능하면 조속히 만나기를 원한다고 연락해 온것이다.

이소식을 접한 가족들의 가슴은 쿵쾅거리기 시작했다. 일본정부는 Megumi가 현재 살았다고 믿었던 것이다. 문제는 그녀를 어떻게 일본으로 데려 오느냐가 즉시 문제점으로 떠 오른 것이다.

가족들은 저녁 황금시간대에 TV에 출연하여 그간의 사실을 폭로하자, 의회에서 의문들이 쏟아지기 시작한 것이다. 5월에는 일본정부가 Megumi사건외에도 이와 비슷한 여러건의 납치사건이 있었음을 확인했었다. Yokotas씨 가족처럼, 딸들, 아들, 그리고 자매들, 형제들 그리고 어머니들을 잃어버리고 고통에 빠져있는 더많은 가족들이 있었다라고.

이런 고통속에 있는 가족들중 7가족이 구룹을 만들어 사랑하는 가족들을 구출해 달라는 요구를 하기 시작했다. "북한에 납치된 희생자 가족들 협회"로 명명하고. 그들은 장시간 서로 알지 못하고있던 얘기들을 나누었다.

대부분의 납치희생자들은 20대 전후의 연인들이었으며, 그후로 일본의 전 해안가의 백사장은 범죄발생지로 재조명되었었다.

Megumi가 납치된지 9개월후인 1978년 8월 12일, 24세의 사무직원 Rumiko Masumoto양이 그녀의 남자친구 Shuichi Ishikawa(23세)와 일몰을 보기위해 Kagoshima인근의 백사장으로 갔었는데, 하루전에는 그녀는 저녁식사를 하면서, 어렵게 연인관계라고 가족들에게 고백하기도 했었다.

그들이 타고간 차는 문이 잠겨진채로 발견됐었다. Rumiko의 지갑과 선글라스와 카메라는 차안 의자에 그대로 있었다. 카메라에는 이들 두연인이 서로 번갈라 가면서 찍었던 사진들이 그대로 였다. 경찰은 그녀의 샌달을 그곳으로 부터 멀지않은 물가에서 발견 했었다.

5년후에 북한은 김정일의 명령에 따라 그러한 납치극을 중지 하겠다고 했었다.

17 September 2002

"이납치극의 주역으로서, 나는 일본 수상이 이른 아침에 평양에 오지 않으면 안된다는것을 알려주게 됨을 유감으로 생각한다."라고 김정일은 통고한다. 그러나 김정일의 공갈은 큰 역활은 못했었지만, 일본 수상 Junichiro Koizumi씨는 북한과의 국교정상화를 협의하기위해 평양으로 날아갔지만, 그의 기대와는 달리, 외교적 복병에 부딪치고 만다.

1990년대에 있었던 기근으로 북한주민 약 2백만명이 죽은후에, 김정일은 식량원조, 일본기업의 북한투자 할것과 그리고 35년간 한반도 식민지화 했던점에 대한 사죄를 요구한 것이다. 그러나 일본은 북한공작원들이 납치해간 일본인들에 대한 모든 내용을 알려주기전에는 어떤 관계도 진전 될수없다고 잘라 말한 것이다.

회담이 있기 30분전에 납치희생자들의 명단이 제출 됐었다 : 북한은 13명의 일본인들을 납치 했었음을 인정한 것이다. 그러나 그들중 5명만 생존해 있다고 했다.

죽은 8명은 물에빠져 죽었거나, 연탄가스질식사로, 27세의 여인은 심장마비로, 북한에서는 개인이 차량소유는 매우 드문데, 두명은 시골길달리다 차량사고로 세상을 떴다는 것이었다. 그들의 유품을 줄수없는데, 홍수때 그들의 묘가 다 떠내려 갔다는 이유였다. 이말에 Koizumi수상은 경악할수밖에 없었다.

"나는 이소식에 너무도 심한 충격을 받았다. 일본인들의 안녕과 안전을 책임지고 있는 일본국의 수상인 나는 굉장한 항의를 할수밖에 없다. 죽은분들에 대한 유품이 하나도 없다는것을 가족들에게 어떻게 전할수 있단 말이냐?"라고 김정일에 일갈한 것이다. 아무 대꾸없이 듣고만 있던 김정일은 메모만 했었다. "잠깐휴식시간을 갖읍시다"라고 한마디 뱉었을 뿐이다.

휴계실에서 모욕적인 상황을 논의 하면서, 내각의 대변인 - 후에 일본 정치사에서 가장 오랜 수상직을 했던 - Shinzo Abe씨가 Koizumi수상에게, 평양이 공식적으로 일본인 납치 희생자들에 대한 사과를 하기전에는 절대로 회담이 정상적으로 진행됐다는 선언문에 서명하지 말것을 주문한 것이다.

다시 양측의 대표자들이 회담을 위해 자리를 했을때, 김정일은 메모한장을 들고 일방적으로 읽어 내려갔었다. " 우리 정부가 할수 있는 역활이 어떤것들인가를 포함하여, 이런문제들을 자세히 조사 했었다. 수십년간 우리 두나라 사이에는 서로 어긋난 관계가 이런 일들이 벌어지게 만든것으로 알고있다. 말할 필요도 없이 끔찍한 사건들입니다.

"내가 이해하기로는 이사건은 특별공작조들이 1970년대와 1980년대에, 애국심과 잘못인식된 영웅주의가 만들어낸 산물입니다"라고.

이뉴스를 문재인 간첩과 그 주사파 좌파 찌라시들은 꼭 얽어야 한다. 이런 악질 흉악범들이 통치하는 북한에 원자력 발전소 건설해주고, 아직 대한민국에는 도입 되지도 않은 Covid-19 Vacchine을 북한과 공동으로 접종하자는 이인영 간첩은 꼭 새겨 읽어야 할것이다.

지식인들, 군리더들, 역사학자들, 공무원들, 그리고 국민들 잠에서 깨어 일어나, 4.19때 처럼 청와대로 진격하여 문재인 간첩과 그일당을 끌어낼 용기를 발휘 하시길 바란다.

아래의 원문을 자세히 읽어 보시기를 간절히 권합니다.

She arrived in North Korea after 40 hours locked in a pitch-black storage room, Ahn said, her fingernails torn and bloody from trying to claw her way out. The agents who took her were chastised for their poor judgement. She was too young; what use did they have for a little girl?

Megumi cried for her mother and refused to eat, unnerving her state minders. To soothe her, they promised that if she worked hard and learned fluent Korean, she would be allowed to go home.

It was a lie to fool a devastated child. Her captors had no such intention. Instead, North Korea would force Megumi to work as a spy trainer, teaching Japanese language and behaviour at an elite school for espionage.

For this to happen once would be extraordinary. But the bungled abduction set a kind of precedent in North Korea.

The country's future leader Kim Jong-il, then head of its intelligence services, wanted to expand his spy programme. Kidnapped foreigners weren't just useful as teachers. They could be spies themselves, or Pyongyang could steal their identities for false passports. They could marry other foreigners (something forbidden to North Koreans), and their children, too, could serve the regime.

The beaches of Japan were full of ordinary people, ripe for abduction, who would stand no chance against highly-trained agents.

"People think I don't remember much about my sister... but I do clearly remember her, even though I was third or fourth grade in elementary school."

When Megumi's younger brother, Takuya Yokota, and his twin Tetsuya were nine, the police hunting for Megumi showed them martial arts videos, urging them - "don't get beaten - be strong."

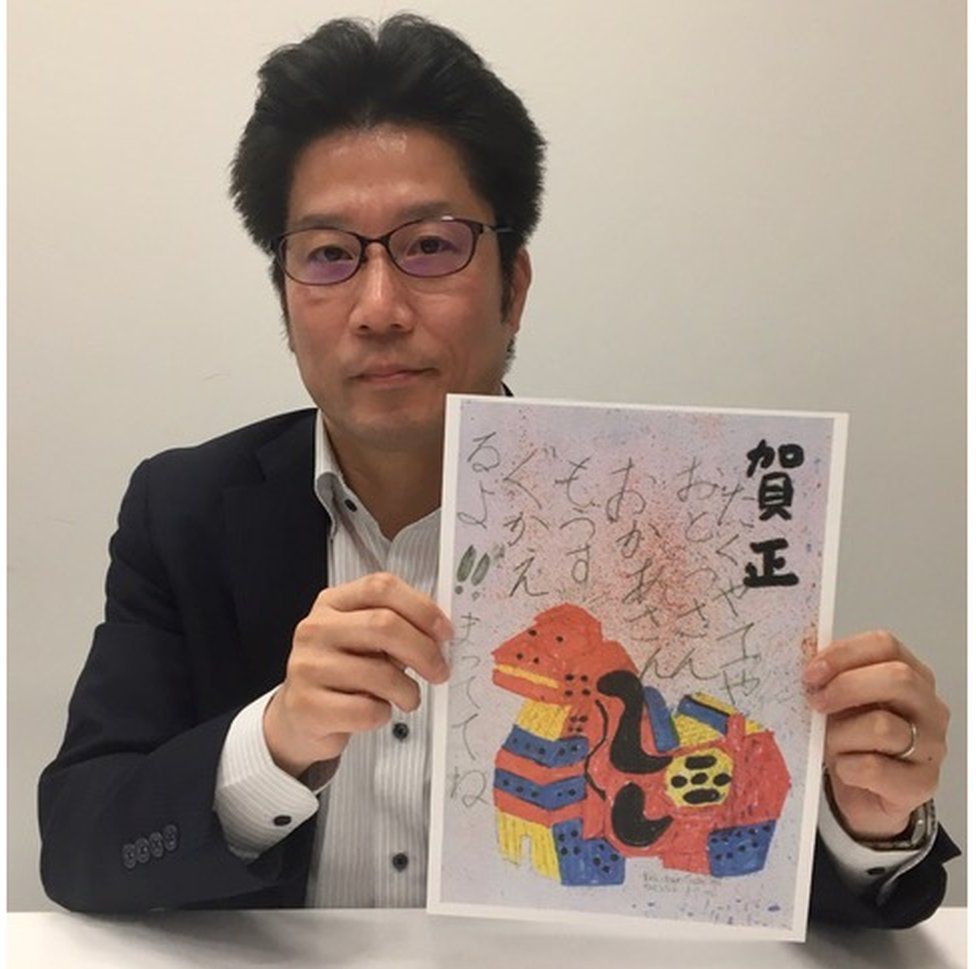

Every day for 43 years, he has tried to heed that advice. Now 52, he sits in a business suit holding a copy of a postcard his sister sent before her kidnapping. At the end she wrote, "I'll be home soon!! Please wait."

"She was very chatty, very active and bright," he says. "She was like a sunflower for our family.

"Without her at the dining table, conversation was limited. The atmosphere got very dark.

"I was very worried, but somehow I went to bed and got up in the morning - every day, to find that she was missing. I got up, and I still couldn't find her."

For the first two decades after Megumi disappeared, the Yokotas had nothing but a cold case and their own desperate need to understand what had happened.

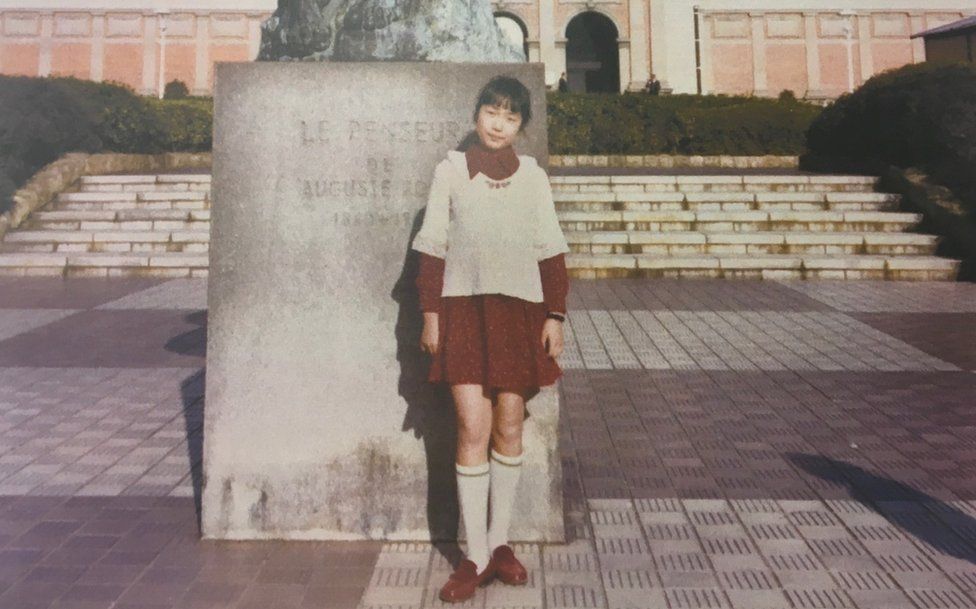

They tried to guess how she might be ageing. She had been tall at 13; was she still? Had she kept her childhood dimples? A shadow hung over every question. They had no clue if she had survived that last November night.

In coastal towns in the late 1970s, rumours hovered like sea gulls. Locals spoke of strange radio signals and lights from unknown ships, or Korean cigarette packets discarded by the shore. In August 1978, a couple on a beach date in Toyama prefecture were gagged, hooded and handcuffed by four men who spoke oddly formal, accented Japanese. They were hastily abandoned when a dog-walker came by and the dog barked, spooking their attackers.

Others were less lucky.

On 7 January 1980, Japan's Sankei Shimbun newspaper ran a front-page story: "Three couples on dates evaporate mysteriously along the coasts of Fukui, Niigata, and Kagoshima - is a foreign intelligence agency involved?"

But it took a convicted terrorist to finally firm up the link to North Korea.

Kim Hyun-hui had killed 115 people by helping to smuggle a bomb onto a South Korean passenger plane in 1987. Staring down a death sentence in Seoul, she testified that she was a North Korean agent acting on state orders. She said she had learned Japanese language and behaviour so she could work undercover. Her teacher, she said, was an abducted Japanese woman whom she lived with for almost two years.

The testimony was compelling. But Japan's government wouldn't officially acknowledge that North Korea was stealing people. The two countries had a hostile history and no diplomatic relations. It was easier to ignore the evidence.

When Japanese negotiators tried to raise the issue privately, the North angrily denied any abductees existed and terminated talks.

It was 1997 - 20 years after Megumi went missing - when Pyongyang finally agreed to investigate.

21 January 1997

"We have information that your daughter is alive in North Korea."

Shigeru was stunned. A Japanese official named Tatsukichi Hyomoto, the personal secretary to an MP, had contacted the Yokotas out of the blue. He had been probing abductions by Pyongyang for a decade, and wanted to meet them as soon as possible.

Along with deep shock, a mad hope sprang back into the family's hearts. The government believed Megumi was alive. So the question at once became: How do we get her back?

The Yokotas went public with their kidnap story. They were terrified North Korea would kill Megumi to cover up what had happened, but her father argued the case would be treated as hearsay unless her name was revealed. They had to spread the news across Japan, and beg the country for help.

The family appeared on primetime TV. Questions were raised in parliament. In May, the government publicly confirmed that Megumi was not an isolated case: There were more like the Yokotas, aching for stolen daughters, sons, sisters, brothers and mothers.

Seven of these families formed a support group to demand the rescue of their loved ones: the Association of Families of Victims Kidnapped by North Korea.

They talked at length, pooling what little they knew. The abductions appeared opportunistic, but patterns soon emerged. Most victims were young lovers in their twenties. Beaches across Japan had been recast as crime scenes.

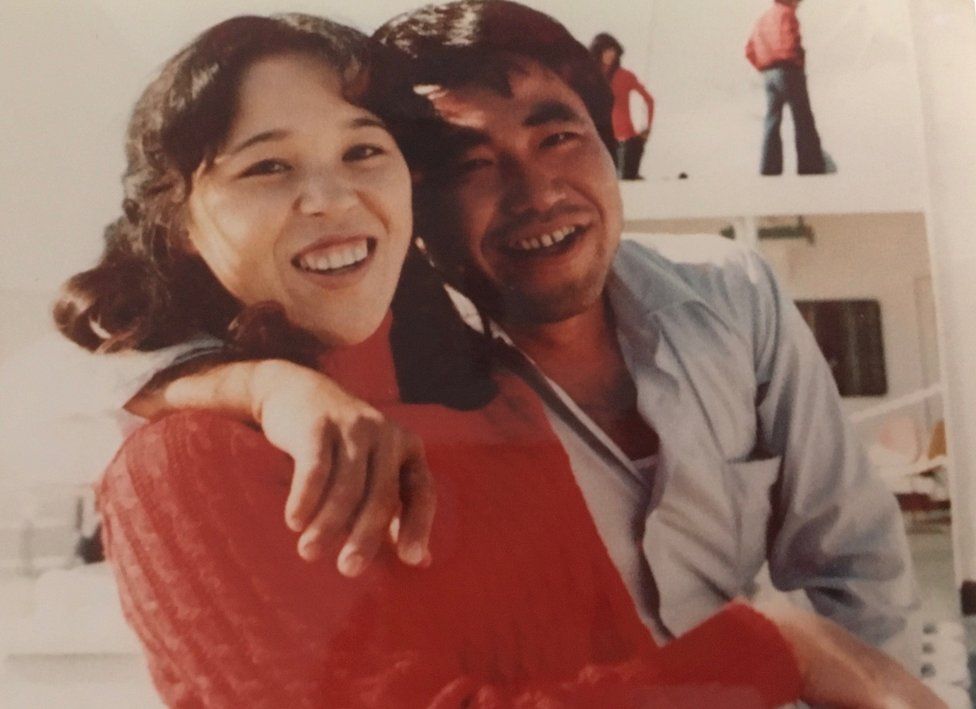

On 12 August 1978, nine months after Megumi disappeared, 24-year-old office clerk Rumiko Masumoto went to watch the sunset with her boyfriend, Shuichi Ishikawa, 23, at a beach in Kagoshima Prefecture. Just a day earlier, she had shyly told her family about their relationship over dinner.

Their car was found locked at the scene, with Rumiko's wallet and sunglasses in the passenger seat. Her camera was there too - filled with pictures the couple took of each other the day they disappeared. Police picked up one of Shuichi's sandals not far from the water's edge.

Every kidnapping was a private tragedy. A loved one who fell out of the world without notice. Some of those left bereft were driven to the edge of madness by their loss.

The press and the public weren't always sympathetic. News reports referred to the abductions as "alleged". Several Japanese politicians believed the claims were South Korean disinformation spread to discredit the North.

But as the families drew up petitions, filled the airwaves, and lobbied the government, the truth was gathering weight like a rolling snowball.

Five years later, in North Korea, it would stop at the feet of Kim Jong-il himself.

17 September 2002

"As the host, I regret that we had to make the prime minister of Japan come to Pyongyang so early in the morning," said North Korea's leader.

But his companion's anger had nothing to do with the time.

Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi had flown in to discuss normalising Japan's relations with North Korea, hoping the step would boost his flagging opinion rating. Instead, he had walked into a diplomatic ambush.

After a brutal 1990s famine believed to have killed more than two million North Koreans, Kim Jong-il wanted food aid and investment, and an apology for Japan's 35-year colonisation of Korea. Japan wanted - and had refused to proceed without - details of every citizen abducted by Pyongyang's spies.

Half an hour before the historic meeting, the list of names appeared: North Korea admitted to kidnapping 13 Japanese citizens. But just five were said to be alive.

The causes of death given for the other eight included drowning, choking on the fumes from a broken coal heater, a heart attack in a woman of 27, and two car accidents in a country where private citizens rarely own cars. Pyongyang claimed it could not provide their remains, as floods had washed away almost all their graves.

Koizumi was aghast.

"I was utterly distressed by the information that was provided," he told Kim Jong-il, "and as the prime minister, who is ultimately responsible for the interests and security of the Japanese people, I must strongly protest. I cannot bear to imagine how the remaining family members will take the news."

Kim listened in silence, taking notes on a memo pad, then enquired: "Shall we take a break now?"

Debating their predicament in an anteroom, deputy Cabinet spokesman Shinzo Abe - who would become Japan's longest-serving prime minister - urged Koizumi not to sign the declaration committing to normalisation talks unless Pyongyang formally apologised for the kidnappings.

When the delegates reconvened, Kim picked up a memo and read: "We have thoroughly investigated this matter, including by examining our government's role in it. Decades of adversarial relations between our two countries provided the background of this incident. It was, nevertheless, an appalling incident.

"It is my understanding that this incident was initiated by special mission organizations in the 1970s and 1980s, driven by blindly motivated patriotism and misguided heroism.

"[…] As soon as their scheme and deeds were brought to my attention, those who were responsible were punished. This kind of thing will never be repeated."

The dictator of Pyongyang said the abductions were designed to provide its spies with native-Japanese teachers, and false identities for missions in South Korea. Some victims were snatched from beaches, yes - and others lured from studies or travels in Europe.

He spoke of Megumi, the youngest named abductee by many years, saying her kidnappers had been tried and found guilty in 1998. One was executed, and the other died during a 15-year sentence, he said.

"I would like to take this opportunity to apologise straightforwardly for the regrettable conduct of those people. I will not allow that to happen again."

Koizumi signed the Pyongyang Declaration.

Five alive, eight declared dead.

Back in Japan, at a Tokyo guesthouse owned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the abductees' families were waiting anxiously for news.

Megumi's parents sat down with the Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister, Shigeo Uetake. He took a breath.

"I regret to inform you..."

North Korea says Megumi Yokota hanged herself in a pine forest on 13 April 1994, on the grounds of a Pyongyang mental hospital where she was being treated for depression.

This is her second death date. The North initially claimed she had died on 13 March 1993, before declaring that an error.

As evidence, Pyongyang produced what it said was a hospital "death registry". It was a form with the words "Registry of Patient Entering and Leaving the Hospital," on the back of it. But "Entering and Leaving the Hospital," had been crossed out several times and the word "Death," written instead. Japan told North Korea it found the document highly suspect.

Another kidnapped Japanese woman, Fukie Chimura, later said that Megumi had moved in next-door to her and her husband in North Korea in June 1994, two months after Megumi's supposed death, and lived there for several months.

The Yokota family don't believe Megumi killed herself. Still, Sakie finds the details of Pyongyang's story chilling.

"In Niigata, we had pine forests," she told the Washington Post in 2002. "I'm sure she missed them. I'm sure she was very lonely. For a minute, I thought maybe she longed so much for us and she couldn't come back that, in an instant, she [took her own life.]

"I cried. But in the next minute, I said no, that could not have happened. I do not want it to have happened. I don't want her to have gone through that."

Two years after declaring Megumi dead, Pyongyang handed over what it said were her ashes. They arrived on the 27th anniversary of her kidnapping. Her parents had kept their daughter's umbilical cord when she was born - a Japanese tradition - and DNA tests were performed.

The samples didn't match.

The scientist who tested the ashes would later say they could have been contaminated, making the result inconclusive. But North Korea had form for providing dubious remains. It had already sent bones it claimed were those of abductee Kaoru Matsuki, a man it said had died aged 42. They included a jawbone fragment which a dental expert said belonged to a woman in her sixties.

On 15 October 2002, the five abductees whom North Korea said were alive landed at Tokyo's Haneda Airport.

They stepped off the plane to Japanese flags and homemade "Welcome home" banners, and sobbed on the runway in the arms of their families.

Pyongyang had agreed the five could visit Japan for a week to 10 days.

They would never set foot in North Korea again.

How do you rescue someone whose captor insists they are dead? Of course, the Yokotas weren't the only family facing this nightmarish question.

Rumiko Masumoto, the young office clerk who disappeared with her new boyfriend, was also on the list of deceased.

North Korea says Rumiko died of a heart attack in her twenties. Her family don't accept that. "There's no one in my family with heart failure," her brother says simply.

Teruaki Masumoto was 22 and studying fishery in Hokkaido at the time of his sister's 1978 abduction. He is 65 now, retired from a job grading tuna at Tokyo's main fish market.

He and Megumi Yokota share a birthday - 5 October - though they are nine years apart. Megumi would be 56 now, and his sister Rumiko 66.

Rumiko doted on her brother, the youngest of four Masumoto siblings.

"She was very kind to me," he says. "Since our family wasn't so affluent, we lived in one room with a family of six. Rumiko and I slept on the same futon until I was about 12 years old. She loved me so much. When I got scolded by my father, she cried and defended me."

Teruaki has charted four decades of lost time on a precious gift from Rumiko: a watch she gave him when he got into university.

In recent years, the war of missing seconds has grown to feel ever more urgent.

Rumiko and Teruaki's father, Shoichi, died of lung cancer in 2002. Their mother Nobuko made it to 90 before passing away in 2017.

For four decades she waited for her daughter to come home. But in her later years, she acknowledged that death might reach her first.

The search for a stolen child, dead or hidden in a pariah state, is a brutal legacy to leave. But it's an issue many abductees' families have been forced to address. With the parents' generation now gone or in their twilight years, should they tell their present, living children to fight on with everything they have? Is it even a choice?

There was no formal handover, but Teruaki tends the dark sand-timer now.

"My father, when he was still alive back in around 2000, became unable to come to Tokyo," he says. "At the time he said to me - 'I'm sorry.' And I felt sort of puzzled and uncomfortable, because I was doing this not because of my father but because of my missing sister.

"My mother sometimes told me that she wondered if Rumiko would ever come back to Japan. So I think my mother half doubted that she would see her alive. But they didn't say things like, 'this is your time' or 'I want you to keep doing this rescue mission.' No, they didn't say that to me."

They didn't need to.

"Yes."

Megumi's brother, Takuya Yokota, was still in his thirties when he felt the mantle settling on his shoulders.

"When I went to the United States to see President Bush in 2006, I found my ageing parents had trouble spending a long time on a plane," he says. "And in Japan too, if we went somewhere far from Tokyo, they would also have trouble travelling. At that time, I understood that my parents would not be able to go to far-away places any more."

Only two of the victims' parents remain alive. Sakie, the youngest, will turn 85 in February.

Megumi's father Shigeru, softly-spoken but steely, died on 5 June 2020. He went into hospital in April 2018, and fought every day that followed to stay alive a little longer, with his treasured daughter's picture by his bed.

In Japan, where everyone knows about "The Abduction Issue", it's not possible to protect a child with personal ties for long. Both Teruaki Masumoto and Takuya Yokota are fathers: Teruaki to a young daughter, and Takuya to a son in his early twenties.

Takuya believes his son was in infant school when they told him what had happened to Aunt Megumi. "Probably when he was six or seven years old. I'm sure I had talked to him at the age of nine, the age I was when my sister got abducted."

Teruaki's daughter was younger still.

"My daughter knows about Rumiko," he says. "My wife told her before she entered kindergarten. There's this festival in Japan in summer, in July, when we think a couple separated by the Milky Way meet once a year up in the sky. We write our wish on a short piece of paper and put it onto a tree. On that paper, my four-year-old daughter wrote, 'I want to see my aunt.'

Not every abductee's family has the luxury of insulating children from the burdens of loss and duty, as Teruaki knows.

Since 2004 he has campaigned alongside Koichiro Iizuka. The person stolen from Koichiro was his mother. He was 16 months old at the time.

Aged 22, Yaeko Taguchi was a nightclub hostess, and single mother to a baby son and three-year-old daughter. When she disappeared with no explanation in June 1978, her children were left abandoned in their Tokyo nursery.

Yaeko's baby son was adopted by her brother, Shigeo Iizuka, and raised as his fourth child. Her daughter was cared for by an aunt.

Now 43, Koichiro Iizuka remembers nothing about his birth mother. He's notably polite, calling her "Yaeko-san" - "Ms Yaeko".

"Mum" and "Dad" are Shigeo and his wife Eiko. And until he reached 22, he had no idea his life was more complex than that.

"When I got a job I had the chance to go abroad for training, and I needed to apply for my passport," he explains. "In order to do that I needed to get a family registration paper. And I took it and looked at it, and found that I was adopted by Mr Iizuka.

"First I couldn't imagine why they had kept this secret for so long; I just couldn't imagine, so I needed some time. It took me a week before I went to my parents.

"When I came home, my mother was out of the house but my father was there. So I told him I had looked at the family registration paper and had found out I was adopted. And I asked him - what happened to me?"

Shigeo took him to lunch and told him the truth. "He told me, as the paper says you're not my biological child. And I have this youngest sister - whose name is Yaeko - and you are a child of hers."

He held back the darkest part until they were home.

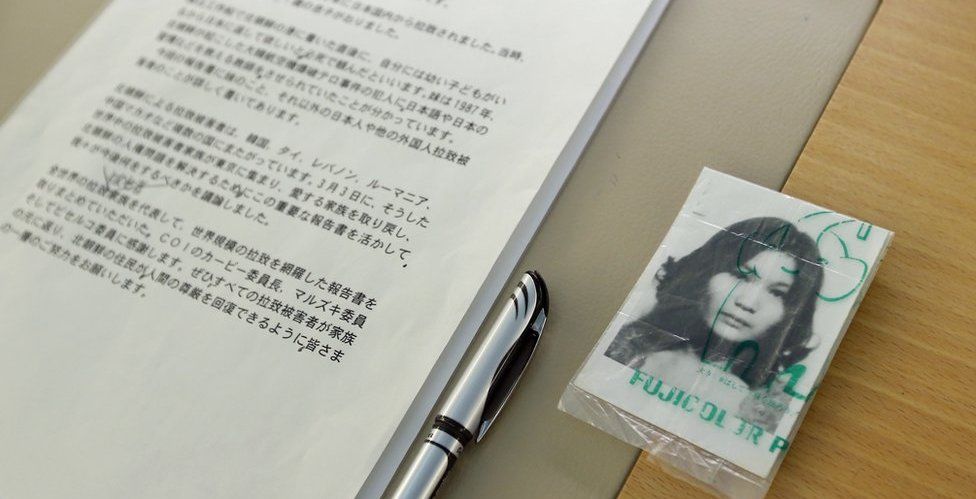

"He told me, there is this person Kim Hyun-hui - the North Korean agent, the bomber of the KAL plane in 1987, and she said she was taught by a Japanese teacher. Kim Hyun-hui was shown several pictures twice [by Japanese police] - and she picked Yaeko-san, saying 'this is my teacher.' From that it was clear that she was one of the abductees in North Korea."

The claim was corroborated by Fukie Chimura, one of the abductees returned to Japan, who said she had shared accommodation with Yaeko.

In 2004, two years after the five Japanese made it home from North Korea, Koichiro decided to reveal publicly that he was Yaeko Taguchi's son. He was frustrated by the diplomatic impasse on rescuing the others, keen to do all he could to push the issue.

"This person Yaeko-san wasn't real in my memory - she was like someone in a story," he says. "But this woman in the story gave birth to me, so it was shocking to me that I wouldn't be able to see her.

"My father was given a lecture by a foreign ministry official who said there was no proof to support North Korea saying that she was dead. And my father said he just couldn't believe it - he couldn't take the word of North Korea.

"So we thought - I thought - that I wanted to rescue her, help her."

The plane bomber Kim Hyun-hui had been sentenced to death for her crimes, but was ultimately pardoned by South Korea's then president. In 2009, Koichiro and Shigeo Iizuka travelled to Busan, South Korea to meet her, and learn what they could about her time with Yaeko.

"She said, I feel that Yaeko-san is my sister, and I'm very happy to see my sister's son today," recalls Koichiro. "And I hope someday that the four of us can meet at one time."

Officially, North Korea says Yaeko Taguchi died in a car accident in 1986. But Ms Kim disputes that, saying she spoke to a driver who reported seeing her alive the following year. She would now be 65.

Koichiro knows he may ultimately be left searching for his mother, the missing stranger, without the backing of those who knew and loved her.

"Of course I feel time is very important. Especially because Yaeko-san has two siblings who have already died. My father is ageing. I want him to see her again very much. Not only my family, but the other abductees' families… I can easily see they're getting older. People who used to be very active - some of them are gone already, and some are very frail."

North Korea has never admitted it was behind the bombing of Korean Air Flight 858, and maintains there is no such person as Kim Hyun-hui.

Yaeko Taguchi's family fear that after tutoring Kim and spending her days surrounded by spies, Yaeko may simply know too much ever to be released.

All those caught up in this struggle share a common dread: That passing time will make a mockery of it, as the abductees age beyond reasonable hope of survival.

Would they have died of old age in North Korea by now? At time of writing - no. But it will fall to the current generation to address the question.

"Time passes equally for both sides," says Takuya Yokota. "Yes, they are getting older too. And I think spending a year or 20 years in Japan or in England or the US has a different meaning to spending the same amount of time in North Korea. In North Korea, it's very hard not only to stay alive until tomorrow, but to keep alive today."

For Teruaki Masumoto, not even their loved ones' deaths would justify giving up.

"If their deaths were proven then we would want their bones to be back with us. That's the Japanese mentality. We would also continue to hold the Japanese government accountable for not being able to rescue the abductees. Even though there are 17 abductees 'approved' by the government, I think many, many more are in North Korea - more than a hundred. If there are other abductees, we should be able to establish what happened to them. So we're not going to stop working any time soon."

In 2014, North Korea agreed to open an investigation into the fates of the eight acknowledged abductees it has not returned, despite having declared them dead. It was dragged out until 2016, then cancelled in a spat over nuclear test sanctions.

Megumi's father dreamed of walking her through the lights and liveliness of Roppongi, Tokyo's entertainment district. But in her mother's prayers, they go to a field together where they can lie down looking at the sky, without anybody around, and just quietly and peacefully spend time.

Sakie writes open letters to her daughter, in the hope the words may somehow reach her.

Part of one, published by JAPAN forward last year before the loss of her husband, reads as follows:

"Dear Megumi,

"I know it might seem a bit strange that I am just casually reaching out to you. Are you well?

"[...] I have been trying my best to live a full life, but I feel my body weakening, and every day gets a little bit harder. When I see your father at the hospital desperately doing his rehabilitation exercises, I am overcome with an urgency to find a way for him to see you.

"This is the reality of ageing. It's not just your father and me. We may be dealing with ageing, sickness, and weariness, but the families of all the victims in North Korea still go on yearning to see their loved ones back on native soil and hold them in their arms.

"We don't have much time left. We've fought long and hard with our hearts and souls, but we cannot hold out much longer.

"[...]I want to celebrate my next birthday with you. Only the nation of Japan - the government - can make that happen. But sometimes I'm overcome with a sense of unease and am concerned that our efforts are futile when I see what's going on in our government. I doubt they have the will to solve this problem and figure out a way to bring the victims home.

"[…] Somehow, I have managed to survive this raging storm. I am thankful that you also have survived, supported by a greater power. We are not alone. And so I pray again today as I think of all of you.

"It will take more effort than ever before to bring all the victims back to Japan. Of course, Japan must stand up for itself, but we also need courage, love, and righteousness from around the world. (Those of you who read my letter, please take a moment to remember in your heart the abductees still trapped in North Korea. Please speak out for them.)

"Dearest Megumi, I will keep up the fight to bring you back home to me, your father, and your brothers Takuya and Tatsuya. My resolve remains unshaken, even at age 84. So please take care of yourself and never lose hope."

All in-person interviews were conducted prior to the coronavirus pandemic

No comments:

Post a Comment