내가 국민학교 다닐때는, 나라 전체가 변소(치간)시설이 여기 사진에서 보는것 처럼, 살고 있는 본채에서 멀리 떨어져있었고, 그곳에서는 대소변만 처리하는게 아니고, 부엌에서 밥지을때 아궁이에 불을 지피고 난후의 재(Ash)를 같은 공간에 버리면, 대변을 한다음 비치되여 있는 나무로 만든 Shovel 떠서 잿더미 속으로 던져, 밭에 비료로 사용하곤 했었던 기억이 있다.

물론 나는 어렸으니까, 직접 재와 배설물이 혼합된 비료를 지계에 짊어지고 밭에까지 가서 뿌린기억은 없었고, 위의 형님 또는 일꾼들이 하는것을 기억할 뿐이다.

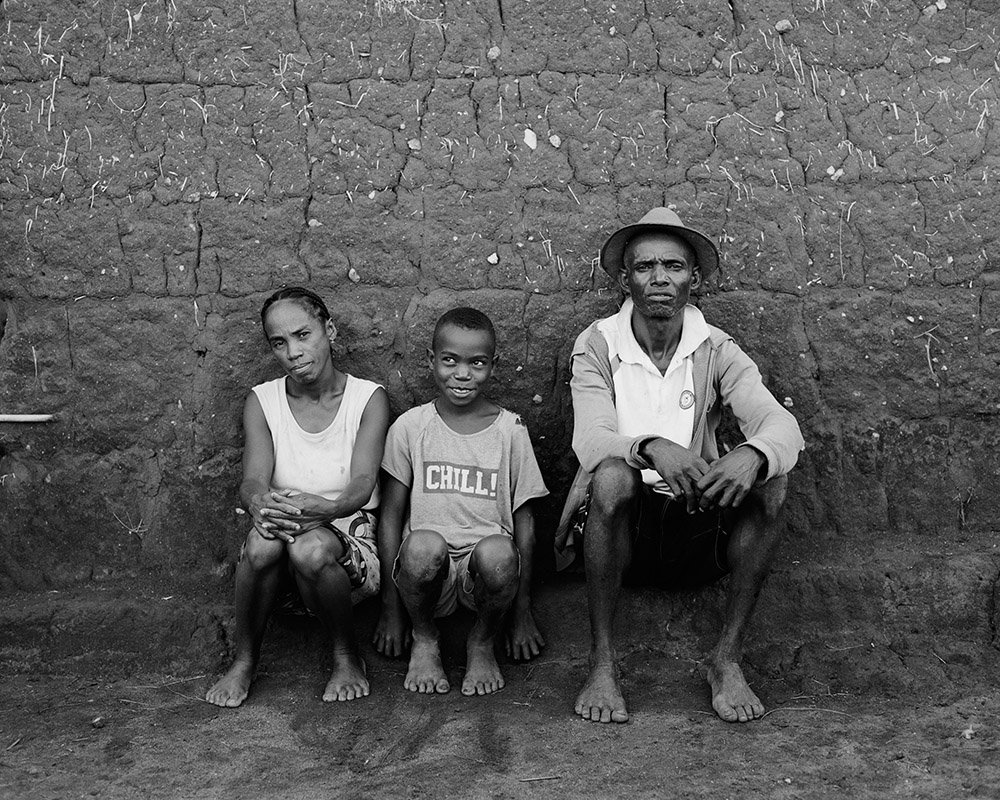

오늘 NGO가 아프리카의 Rwanda 와Madagascar의, 그들의 눈높이에서 봤을때는 분명히 보물같은 희귀한 존재의 변소 시설을 보면서, 취재감이 되고도 남았을 걸작품이었을 것으로 이해된다. 물론 이나라들의 시골지역에서 촬영한 것이고, 나역시 아프리카 여러나라를 탐방했었지만, 사진에서 본것 같은 변소는 기억속에 별로 없었다.

애티오피아, 남아프리카, 이집트를 포함한 여러나라에서의 탐방시에, 주로 시골변방지역을 많이 봤었지만....

http://lifemeansgo.blogspot.com/2020/12/323-2013-3.html

젊은 세대들에게는 생소하고, 이해가 잘 되지도 않을 것으로 생각된다. 1987년도에, 지금은 40대 중반의 세월을 살아가고 있는 두 아이들과 시골친척들과 형제 자매댁을 방문했을때의 기억중 하나가 이사진을 보면서, 생각나는 변소에 대한 것이 있다.

딸아이가 변소에서 볼일을 못보고 벌벌 떨다가 그냥 나왔던 것을 엄마가 우연히 봤다가, 겨우 이해을 시켜서 볼일을 보게 했었던 기억이다. 시골의 재래식 변소를 생전에 처음 본 딸아이로서는 어쩌면 당연한 반응이었을지도 모른다.

누나댁은 시골읍에서 둘째 첫째가는 부자였었는데.....이에 충격을 받은 누나댁은 본채를 다 헐어내고 요즘으로 치면, 서양식으로 새로 크게 집을 지어 현대식 시설을 갖춘 대저택으로 만들었었다. 딸아이가 그렇게 하도록 원인 제공을 한 수훈자이기도 했지만, 딸아이가 방문을 하지 않았었더라면, 어쩌면 아무런 불편없이 사용했던, 시골생활의 사고방식을 더 오래 유지 했었을 것이란 생각도 해보면서.... 혼자서 그긴 역사속의 한장면을 그려보면서 피식 웃는다.

The dream for photographer Elena Heatherwick was to work for non-governmental organisations (NGOs), documenting lives and seeing the pictures she had made being used to effect change.

A recent commission from Water Aid gave her the opportunity to do just that, photographing remote communities in Rwanda and Madagascar, in the company of journalist Sally Williams.

But commissions like this did not come overnight.

After completing her studies in photojournalism, she became a mother and put the notion of foreign travel on hold, turning her lens instead on culinary creations for the Guardian food pages.

But persistence pays off, and she was eventually commissioned by the United Nations to photograph midwives in Haiti. The call came after the picture editor remembered her work from a competition the UN ran, asking people to submit a photo of someone they admired.

Heatherwick's photograph was of her mother, a doula, and though that image was one of many on an Instagram story, it was enough to clinch the commission.

While in Haiti she met one of Water Aid's staff and was immediately struck by the scale of the issue, that two billion people around the world did not have access to even a basic private toilet.

Heatherwick started to plan how she could take pictures that best represented the problem. She was fascinated by pictures of the toilet structures themselves, and soon decided this was what she wanted to photograph, alongside the communities.

Heatherwick and Williams had initially planned to travel to a number of countries, but Covid stopped them in their tracks, so they made it only as far as Rwanda and Madagascar.

In Madagascar, 90% of the population - more than 22 million people - do not have a decent toilet, and a third of Rwandans - four million people - are in a similar situation.

However, Heatherwick and Williams set out to visit two villages where things are much improved.

In Ambatoantrano, a remote village in the central highlands of Madagascar, and the village of Gitwa, in the mountains of southern Rwanda, nearly all households now have their own facilities.

As they arrived at each village they bought wood, hired carpenters and prepared a large white backdrop against which the toilets would be photographed.

Heatherwick wanted to treat the structures in the same way that an architectural photographer would document the latest high-rise building in a modern city.

"By isolating the structures from their surroundings, we hoped to showcase their designs, to make people look differently at an everyday object and to celebrate the heroes pushing for better sanitation across the world," says Heatherwick.

In addition, she wanted to make sure each one was photographed in a way that would highlight its beauty.

"When buildings are finished the photographer always shoots in the most epic light - so I wanted to apply that same reverence to these structures."

In reality of course, there were storms and cloudy days, so Heatherwick shot in black and white, allowing her to focus attention on the form, shape and their beauty. It also gives the work a uniform feel.

"Through talking to people in the communities it is clear that a solution for one is not something you can apply to the whole country, or the world," says Heatherwick.

However, in both countries Heatherwick and Williams found people were proud of the toilets they had built. Some were constructed by the whole village; others made their own.

But for Heatherwick, "it is the stories behind the toilets, the people, who have or don't have one, that is important".

The plan had been to show the work in a gallery, but for now you can see it online.

All photographs courtesy Elena Heatherwick / WaterAid / People's Postcode Lottery

No comments:

Post a Comment