이번 조사에 응한 43,000명의 응답이 전체 캐네디언들의 생각을 대변하는것으로 믿기는 어렵지만, 응답자들의 대답은 매우 신속하고 간단하게 표현됐었다.

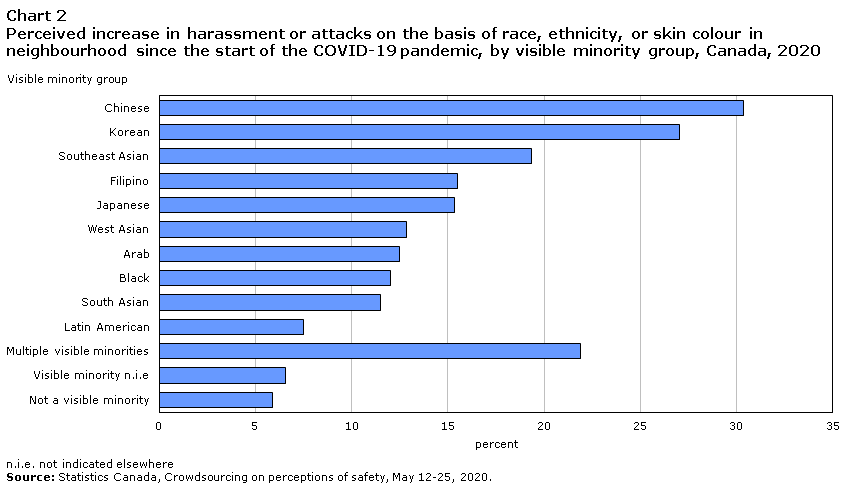

응답자의 30%이상이 중국출신의 캐네디언들이었는데, 이번 Pandemic기간동안에 괴롭힘과 인신공격을 당했던것을 나타났으며, 그다음으로 한국출신 캐네디언으로 전체 응답자의 27%을 차지했다. 그다음으로 유색인종구룹으로 분류되는 22%, 그리고 동남 아시아출신들이 19%였었다. 맨 마지막으로 유색인종이 아닌, 전체인구 구룹으로 속하는데 약 6% 였다.

소수민족 구룹에 속하는 응답자의 대부분이 Pandemic 이전보다 인종차별공격이 다른때의 3배이상 증가했다고 대답한 것이다.

지난 3월 중순경 Pandemic이 퍼지고 있을때, 몬트리얼소재 한국총영사관에서는 인근에 거주하는 한국계 캐네디언들에게, 앞으로 인종분규로 인한 신체적공격이 발생할것에 대비하라는 경고(warned those of Korean heritage)를 보냈었다. 그이후로 여러건의 아시안계통의 캐네디언들(several incidents targeting Asian Montrealers)에게 비슷한 사건이 터지기시작한 것이다.

지난 5월에 뱅쿠버에서는 29건의 아시안들에 대한 증오범죄가 발생했었는데 지난해 같은 기간에 4 발생했던 사고보다 더 증가한 것이었다. 같은 기간에 조사된 여론조사(A poll taken around the same time)에 따르면 24%의 B.C거주 동남아시아 출신 주민들은, Pandemic이후, 인신공격, 욕설의 괴로움을 당했었다고 응답했다.

현재까지는 믿을만한 확실한 인종분규에 대한 정부의 통계가 발표되지는 않았지만, 지역사회가 중심이 되여 반아시안에 대한 괴롭힘이나 공격에 대한 보고서는 5월 중순(reports of 120 such incident)현재 120건의 사건이 발생했다고 한다.

사건보고서에 나타난 4/5정도는 욕설이었고, 다른 20%는 침뱉기, 일부러기침하기, 또는 신체공격이 포함되여 있다고 했다. 대부분의 사건들은 공공장소에서 발생했었고, 그들중 절반 정도는 길가의 주차장에서 또는 큰 도로의 보행로에서 발생 했다고 한다.

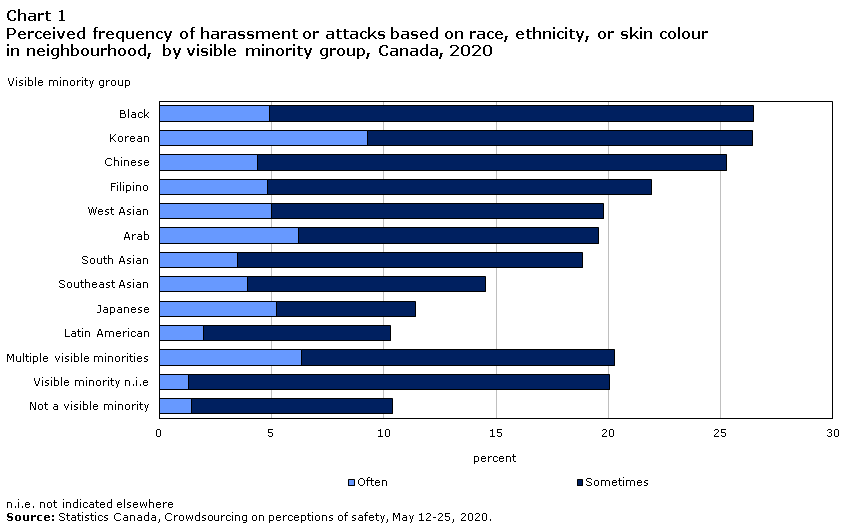

캐나다 통계청은 공격을 당한 응답자들에게 인종차별, 소수민족 괴롭힘과 공격등의 사고가 얼마만큼씩 주기로 느꼈었는가를 설문조사 했었다.

흑인과 한국계 출신들의 대답은 이와같은 인종차별 사건들은 수시로 발생했다고 했는데, 26.5%는 그들의 이웃들과 발생했었고, 그다음으로 중국인들은 25%, 필리핀출신들은 22%로 응답했다.

라틴 아메리칸출신들과 유색인종에 속하지 않는 구룹의 사람들은 그들의 이웃들로 부터 괴롭힘 당한통계가 미약했으며, 10.4%의 응답자들은 거의 느끼지 못했지만, 때때로 가끔씩 느낀적은 있었다고 했다.

"캐네다 인구의 상당포션을 차지하고있는 유색인종들은 대체적으로, 다른 구룹의 인구에 속하는 사람들보다 더많이 불안함을 느낀다고 보고됐다"라고 캐나다통계청은 도표를 인용하여 설명하기도했다.

"안전하지 않다고 느낀다는것은 사회적으로나 개인적인 차원에서 봤을때, 사회적융화감 또는 신체적 또는 정신적 또는 웰비잉면에서 부정적인 면으로 작용한다는 것이다."라고.

그래도 조그만 땅덩어리의 한국에서 느꼈던것 보다는 나의 경우는 더 불안감을 느낀다. 시골촌놈인 내가 처음 서울에 왔을때, 나와 대화를 나눈 많은 사람들은 "전라도 개똥쇄"라는 더러운 단어를 많이 사용했었던 기억이 지금도 있다. 요즘에는 정치적으로 더 외골수에 빠진 전라도 사람들의 반감은, 그래서 문재인 대통령의 정책이 좋아서가 아니라, 어긋장 놓은 생각으로 문통과 그세력들을 지지하는것으로 나는 이해하고 있다. 한국의 지방색 탕평책은 정말로 시급하다고 믿는다. 조국이 부강하고 잘사는 나라로 번영하기를 빌면서...

TORONTO -- Canadians with Asian backgrounds are far more likely than anyone else to report noticing increased racial or ethnic harassment or violence in their neighbourhood during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to new research from Statistics Canada.

Additionally, the data shows, white Canadians are the least likely to believe racist attacks or harassment regularly occur in their neighbourhood or are happening more often since the pandemic began.

The data was released Wednesday as part of StatCan's attempt to gather information about how Canadians are responding to the pandemic via crowdsourcing. Although this approach gives StatCan quick and easy access to a large pool of respondents – more than 43,000 for this particular research – that pool is not reflective of the overall population, meaning the results cannot be used to draw conclusions about Canadians as a whole.

INSIDE THE NUMBERS

Among survey respondents, more than 30 per cent of those who identified as Chinese said they have perceived an "increase in harassment or attacks on the basis of race, ethnicity, or skin colour" in their neighbourhood since the start of the pandemic. The next-highest total came from those who identified as Korean, at 27 per cent, followed by those who said they belong to multiple visible minority groups (22 per cent) and those who identified as Southeast Asian (19 per cent).

At the bottom of the list were those who did not indicate any visible minority status and those who said they belong to population groups that are not considered visible minorities, both at approximately six per cent.

Respondents in visible minority groups were three times as likely to believe discriminatory attacks have increased since the pandemic began than those who did not report being visible minorities, StatCan said.

These findings are just the latest evidence that Asians in Canada have felt increasingly targeted by racist attacks and words during the pandemic.

In mid-March, just as the pandemic was taking hold, South Korea's consulate in Montreal warned those of Korean heritage in the city to be cautious about potential race-based attacks. Since then, several incidents targeting Asian Montrealers have come to light.

Police in Vancouver reported in May that they were investigating 29 possible anti-Asian hate crimes, up from four during the same time period. A poll taken around the same time found that 24 per cent of B.C. residents of East Asian or South Asian descent said they had received slurs or insults since the pandemic began.

There is no comprehensive data yet on the number of race-based attacks in Canada this year, but Project 1907, a community-led attempt to track anti-Asian harassment, had received reports of 120 such incidents as of mid-May.

Four-fifths of those reports were verbal, and the other 20 per cent involved physical actions including spitting, targeted coughing and outright violence. Almost all happened in public spaces, with more than half taking place on a street or sidewalk.

FEELING UNSAFE

StatCan also asked those who took the survey about their perception of the frequency of racial and ethnic harassment and attacks in their neighbourhood in general.

Black and Korean respondents were the most likely to say they believed these discriminatory incidents happen often or sometimes in their neighbourhoods, at about 26.5 per cent each, followed by Chinese respondents at over 25 per cent and Filipino respondents at nearly 22 per cent.

Latin Americans and those who reported not being any visible minority were the least likely to report believing these incidents happen in their neighbourhoods, with 10.4 per cent of respondents in each group saying they think they happen sometimes or often.

Overall, 21 per cent of respondents from visible minority groups reported that they believe discriminatory attacks or harassment occur sometimes or often in their neighbourhood – double the rate of those not considered visible minorities.

Those in visible minority groups were also slightly more likely than others to perceive that crime has increased in their neighbourhood during the pandemic, with Chinese and Japanese respondents most likely to do so.

"Although representing a notable proportion of the Canadian population, visible minorities generally report feeling less safe than the rest of the population," StatCan said in a commentary accompanying the data.

"Feeling unsafe can have negative impacts at both the social and the individual level, by reducing social cohesion or resulting in poorer physical or mental health and well-being."

No comments:

Post a Comment